The two key parameters for traditional investing are financial risk and financial return. Impact investing adds a further two: impact generation — the impact that stands to be generated — and impact risk — the risk that the impact will in fact not materialise.

- financial risk

- financial return

- impact risk

- impact generation

Impact analysis and financial due diligence furnish investors with a sense of what an investment has to offer with respect to all four. The question of investment decision-making, and of potentially preferring one investment over another, is therefore one of looking at performance across these four parameters, and finding the right balance among them. Priorities will change from one investor to another, but the essential concerns and trade-offs are the same.

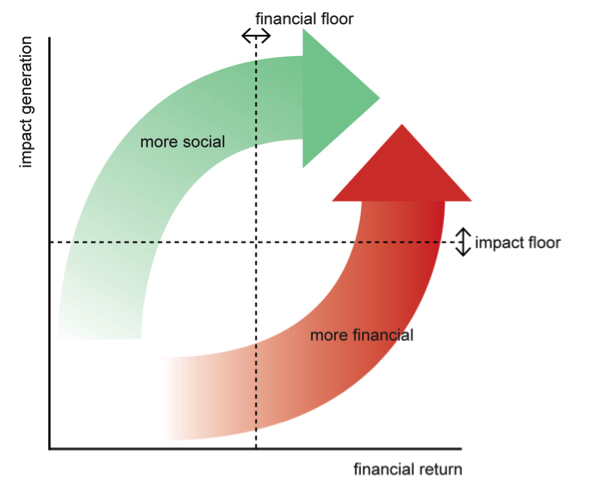

The most well-known and discussed relationship is between impact generation and financial return. This is often represented as a field of values between the two.

The mix of impact and financial return that an impact investment offers positions it somewhere within this field. Impact investors, according to their social and financial appetites, will focus on investments falling within certain areas. An investor may have a “financial floor”, and look specifically for investments meeting a minimum return (this may be the case for example for a fund with a target return to achieve itself). There may equally be an “impact floor”, stipulating a minimum level of acceptable impact generation. Investors will look to optimise among investments to the right of and above their respective floors.

The upper left area is generally characterised by more socially-motivated investments and investors; the lower right by more financially-motivated (profit-maximising) investments and investors. The upper right area of the field promises a “sweet spot” of high impact high return investments.

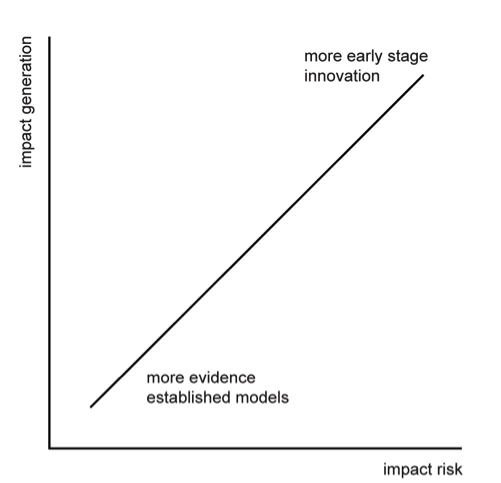

The four parameters however suggest further relationships, including that between impact generation and impact risk:

The potential trade-off between impact generation and impact risk suggests an upward sloping “indifference curve”1, whereby investors seek compensation for higher levels of impact risk with higher levels of impact generation, and vice versa. Investments that lie on the higher sections of the curve are likely to be increasingly characterised by less well tested, less evidenced approaches, but which are innovative, and present the potential for high levels of impact generation (e.g. through effecting a game-change in the prevailing dynamics). Investments that lie on the lower sections of the curve are more likely to be in established approaches and fields of operation, where investors know more what they are going to get, but the impact that stands to be generated is comparatively modest. Investments that sit above the curve, thus offering more impact generation for the same level of impact risk, will be preferable (and will in effect fall on a higher indifference curve), while investments that sit below the curve, thus presenting more risk for the same level of impact generation, will be less attractive (and fall on a lower indifference curve). Investments falling on the same curve will have an equivalence of appeal. An investor’s approach to this trade-off (and the gradient of their particular indifference curves) will depend on their appetite for impact risk.

Impact risk can be expected to decrease over the life of the investment, as the results being generated serve to evidence the approach. This can shift an organisation onto a higher indifference curve. Conversely, if performance shows poor results and increasing impact risk, the investment will shift to a lower indifference curve. Portfolio management can be conducted on this basis.

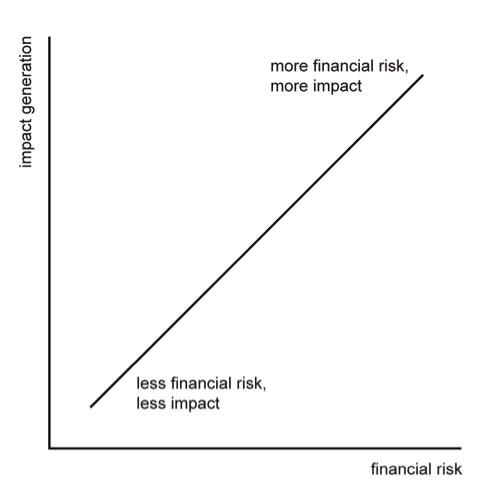

Equally there will be a relationship between impact generation and financial risk:

The potential trade-off between impact generation and financial risk suggests an upward sloping “indifference curve”, whereby investors seek compensation for higher levels of financial risk with higher levels of impact generation, and vice versa. Investment propositions positioned on curves above this one will always be preferred (more impact for less financial risk), while those positioned below will be less preferable (less impact for the same financial risk).

N.B. While a financially risky investment is by implication risky with respect to impact (as a financial wind down implies an end to impact-generating activities), an organisation may be sound financially, but present a weak mission, an uncertainly reasoned theory of change, low levels of evidence etc., leading to an assessment of high impact risk (see impact risk). Alternatively an organisation may have an excellent impact plan, inspiring relatively low levels of impact risk, but exhibit financial weaknesses. Thus impact risk and financial risk remain separate parameters, with potential trade-offs between them.

These graphs show concept sketches for some of the kinds of trade-offs that impact investing can present. Although the relationships above are all with impact generation, trade-offs may occur between any of the parameters: for example, an investor may feel that a low level of impact risk compensates for a low financial return, or that a high financial return compensates a high financial risk. A low impact risk may compensate a high financial risk, and so on.

When dealing with impact investments across a portfolio, it may be desirable to maintain a certain balance among the investments, and ensure that, for example, a certain proportion of the portfolio is low financial risk, or meets a specified return (thus freeing up other parts of the portfolio to be higher risk or lower return). Targets or limits may apply, for example:

- financial targets: the portfolio targets a stated return (e.g. for investors in a fund). Lenders may have a standard lending rate, defining the financial return, but look for a balance of performance across the other three variables.

- impact targets: the portfolio targets certain volumes of outputs or outcomes (e.g. a certain number of beneficiaries reached, homes built, tonnes of carbon emissions saved)

- evidence targets: the portfolio is committed to investing in new approaches and proving them (high impact risk), or alternatively to investing in proven approaches (low impact risk)

- portfolio diversification: to maintain diversification, limits are set as to the proportion of investments of various levels or kinds of financial or impact risk

To be able to think about portfolio management in this way, the profile of each investment must include information regarding its levels of impact risk, impact generation, financial risk and financial return. This enables managers to take an overall position on the fund in relation to all four, and consider new potential investees in relation to the desired fund balance.

Also potentially relevant to the question of trade-offs is the anticipated development of the investment. As the organisation grows and strengthens through its use of investment capital, it may come to present a lower financial risk. Equally, while the impact risk of an investment with an untested approach may initially be high, there is a natural expectation that over the course of the term, the measurement system will start to produce results, and serve to demonstrate what the outcomes of the impact plan really are. As the evidenceable elements within the plan increasingly become evidenced, and the theory of change proved, there is a corresponding decrease in impact risk, and a shift in the balance of parameters. Conversely if the investee organisation is not able to start demonstrating impact (either because measurements are not being taken or because the plan is in fact not working), then impact risk will naturally rise. Observing this, the investor may choose to exert pressure on the organisation to rethink its strategy, and consider what changes it could make to improve its performance.

Therefore the parameters are best understood as potentially dynamic, and accordingly investors will want to continue monitoring and updating assessments beyond the initial analysis. At the point of investment decision-making, anticipated shifts in the levels of impact risk can be considered and taken into account. To help ensure these expectations are met, conditions and understandings may be built into the investment deal.

Typically investment decisions will be made by an investment committee, with the results from the impact analysis stage, and the financial due diligence that is conducted in parallel, being passed up to the committee for consideration. It is essential that all members of the investment committee are familiar with the essential concepts of impact risk and impact generation, and with the impact analysis process (much as it is expected that investment committee members understand the financial aspects of investing, and are capable readers of financial analysis). This allows the committee to integrate the four parameters into their thinking and conclusions.

Following the investment committee’s decision, an investment memorandum can be drawn together, including the results of the impact analysis and financial due diligence, minutes from the committee meeting, the final assessments of impact and financial risk, and the anticipated impact generation and financial return. This can provide a useful consolidated document of the impact investment process to this point, and can be used as a reference tool in the construction of the investment deal.

1 An “indifference curve” is a useful economics concept used to illustrate an individual’s preferences between various baskets of different goods. For example, an individual may be “indifferent” between a basket that is made up of 2 cookies + 3 donuts, and a basket that is made up of 2 donuts + 3 cookies. These two baskets would be on the same “indifference curve”. However, the individual will always prefer more of both, so a basket made up of 4 cookies + 5 donuts will lie on a higher curve, signifying that the individual prefers this bundle and is not indifferent to it. ↑